What's Wrong With the Teenage Mind?

"What was he thinking?" It's the familiar cry of

bewildered parents trying to understand why their teenagers act the way

they do.

How does the boy who can thoughtfully explain the reasons never to

drink and drive end up in a drunken crash? Why does the girl who knows

all about birth control find herself pregnant by a boy she doesn't even

like? What happened to the gifted, imaginative child who excelled

through high school but then dropped out of college, drifted from job to

job and now lives in his parents' basement?

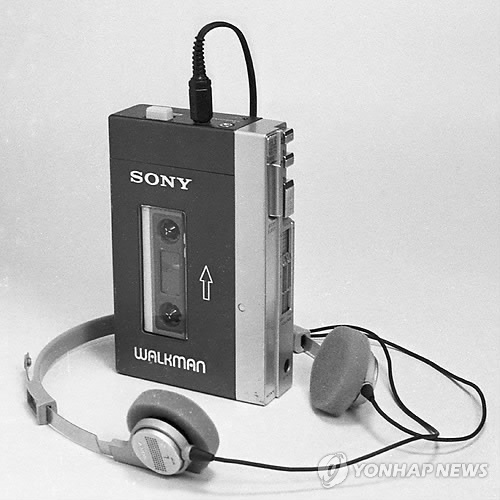

![[TEENCOVER]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AF827B_TEENC_DV_20120127193902.jpg) Harry Campbell

Harry Campbell

If you think of the teenage

brain as a car, today's adolescents acquire an accelerator a long time

before they can steer and brake.

Adolescence has always been troubled,

but for reasons that are somewhat mysterious, puberty is now kicking in

at an earlier and earlier age. A leading theory points to changes in

energy balance as children eat more and move less.

At the same time, first with the industrial

revolution and then even more dramatically with the information

revolution, children have come to take on adult roles later and later.

Five hundred years ago, Shakespeare knew that the emotionally intense

combination of teenage sexuality and peer-induced risk could be

tragic—witness "Romeo and Juliet." But, on the other hand, if not for

fate, 13-year-old Juliet would have become a wife and mother within a

year or two.

Our Juliets (as parents longing for grandchildren will recognize with

a sigh) may experience the tumult of love for 20 years before they

settle down into motherhood. And our Romeos may be poetic lunatics under

the influence of Queen Mab until they are well into graduate school.

What happens when children reach

puberty earlier and adulthood later? The answer is: a good deal of

teenage weirdness. Fortunately, developmental psychologists and

neuroscientists are starting to explain the foundations of that

weirdness.

Photos: The Trials of Teenagers

Everett Collection

James Dean in the 1955 film 'Rebel Without A Cause'

The crucial new idea is that there are two

different neural and psychological systems that interact to turn

children into adults. Over the past two centuries, and even more over

the past generation, the developmental timing of these two systems has

changed. That, in turn, has profoundly changed adolescence and produced

new kinds of adolescent woe. The big question for anyone who deals with

young people today is how we can go about bringing these cogs of the

teenage mind into sync once again.

The first of these systems has to do with emotion and motivation. It

is very closely linked to the biological and chemical changes of puberty

and involves the areas of the brain that respond to rewards. This is

the system that turns placid 10-year-olds into restless, exuberant,

emotionally intense teenagers, desperate to attain every goal, fulfill

every desire and experience every sensation. Later, it turns them back

into relatively placid adults.

Recent studies in the neuroscientist B.J. Casey's lab at Cornell

University suggest that adolescents aren't reckless because they

underestimate risks, but because they overestimate rewards—or, rather,

find rewards more rewarding than adults do. The reward centers of the

adolescent brain are much more active than those of either children or

adults. Think about the incomparable intensity of first love, the

never-to-be-recaptured glory of the high-school basketball championship.

What teenagers want most of all are social rewards, especially the

respect of their peers. In a recent study by the developmental

psychologist Laurence Steinberg at Temple University, teenagers did a

simulated high-risk driving task while they were lying in an fMRI

brain-imaging machine. The reward system of their brains lighted up much

more when they thought another teenager was watching what they did—and

they took more risks.

From an evolutionary point of view, this all makes perfect sense. One

of the most distinctive evolutionary features of human beings is our

unusually long, protected childhood. Human children depend on adults for

much longer than those of any other primate. That long protected period

also allows us to learn much more than any other animal. But

eventually, we have to leave the safe bubble of family life, take what

we learned as children and apply it to the real adult world.

Becoming an adult means leaving the world of your parents and

starting to make your way toward the future that you will share with

your peers. Puberty not only turns on the motivational and emotional

system with new force, it also turns it away from the family and toward

the world of equals.

The second crucial system in our brains has to do with control; it

channels and harnesses all that seething energy. In particular, the

prefrontal cortex reaches out to guide other parts of the brain,

including the parts that govern motivation and emotion. This is the

system that inhibits impulses and guides decision-making, that

encourages long-term planning and delays gratification.

This control system depends much more

on learning. It becomes increasingly effective throughout childhood and

continues to develop during adolescence and adulthood, as we gain more

experience. You come to make better decisions by making not-so-good

decisions and then correcting them. You get to be a good planner by

making plans, implementing them and seeing the results again and again.

Expertise comes with experience. As the old joke has it, the answer to

the tourist's question "How do you get to Carnegie Hall?" is "Practice,

practice, practice."

In the distant (and even the not-so-distant) historical past, these

systems of motivation and control were largely in sync. In

gatherer-hunter and farming societies, childhood education involves

formal and informal apprenticeship. Children have lots of chances to

practice the skills that they need to accomplish their goals as adults,

and so to become expert planners and actors. The cultural psychologist

Barbara Rogoff studied this kind of informal education in a Guatemalan

Indian society, where she found that apprenticeship allowed even young

children to become adept at difficult and dangerous tasks like using a

machete.

In the past, to become a good gatherer or hunter, cook or caregiver,

you would actually practice gathering, hunting, cooking and taking care

of children all through middle childhood and early adolescence—tuning up

just the prefrontal wiring you'd need as an adult. But you'd do all

that under expert adult supervision and in the protected world of

childhood, where the impact of your inevitable failures would be

blunted. When the motivational juice of puberty arrived, you'd be ready

to go after the real rewards, in the world outside, with new intensity

and exuberance, but you'd also have the skill and control to do it

effectively and reasonably safely.

In contemporary life, the relationship between these two systems has

changed dramatically. Puberty arrives earlier, and the motivational

system kicks in earlier too.

At the same time, contemporary children have very little experience

with the kinds of tasks that they'll have to perform as grown-ups.

Children have increasingly little chance to practice even basic skills

like cooking and caregiving. Contemporary adolescents and

pre-adolescents often don't do much of anything except go to school.

Even the paper route and the baby-sitting job have largely disappeared.

The experience of trying to achieve a real goal in real time in the

real world is increasingly delayed, and the growth of the control system

depends on just those experiences. The pediatrician and developmental

psychologist Ronald Dahl at the University of California, Berkeley, has a

good metaphor for the result: Today's adolescents develop an

accelerator a long time before they can steer and brake.

This doesn't mean that adolescents are stupider than they used to be.

In many ways, they are much smarter. An ever longer protected period of

immaturity and dependence—a childhood that extends through

college—means that young humans can learn more than ever before. There

is strong evidence that IQ has increased dramatically as more children

spend more time in school, and there is even some evidence that higher

IQ is correlated with delayed frontal lobe development.

All that school means that children know more about more different

subjects than they ever did in the days of apprenticeships. Becoming a

really expert cook doesn't tell you about the nature of heat or the

chemical composition of salt—the sorts of things you learn in school.

But there are different ways of being

smart. Knowing physics and chemistry is no help with a soufflé.

Wide-ranging, flexible and broad learning, the kind we encourage in

high-school and college, may actually be in tension with the ability to

develop finely-honed, controlled, focused expertise in a particular

skill, the kind of learning that once routinely took place in human

societies. For most of our history, children have started their

internships when they were seven, not 27.

The old have always complained about

the young, of course. But this new explanation based on developmental

timing elegantly accounts for the paradoxes of our particular crop of

adolescents.

There do seem to be many young adults

who are enormously smart and knowledgeable but directionless, who are

enthusiastic and exuberant but unable to commit to a particular kind of

work or a particular love until well into their 20s or 30s. And there is

the graver case of children who are faced with the uncompromising

reality of the drive for sex, power and respect, without the expertise

and impulse control it takes to ward off unwanted pregnancy or violence.

This new explanation also illustrates two really important and often

overlooked facts about the mind and brain. First, experience shapes the

brain. People often think that if some ability is located in a

particular part of the brain, that must mean that it's "hard-wired" and

inflexible. But, in fact, the brain is so powerful precisely because it

is so sensitive to experience. It's as true to say that our experience

of controlling our impulses make the prefrontal cortex develop as it is

to say that prefrontal development makes us better at controlling our

impulses. Our social and cultural life shapes our biology.

Second, development plays a crucial

role in explaining human nature. The old "evolutionary psychology"

picture was that genes were directly responsible for some particular

pattern of adult behavior—a "module." In fact, there is more and more

evidence that genes are just the first step in complex developmental

sequences, cascades of interactions between organism and environment,

and that those developmental processes shape the adult brain. Even small

changes in developmental timing can lead to big changes in who we

become.

Fortunately, these characteristics of

the brain mean that dealing with modern adolescence is not as hopeless

as it might sound. Though we aren't likely to return to an agricultural

life or to stop feeding our children well and sending them to school,

the very flexibility of the developing brain points to solutions.

Brain research is often taken to mean that adolescents are really

just defective adults—grown-ups with a missing part. Public policy

debates about teenagers thus often turn on the question of when,

exactly, certain areas of the brain develop, and so at what age children

should be allowed to drive or marry or vote—or be held fully

responsible for crimes. But the new view of the adolescent brain isn't

that the prefrontal lobes just fail to show up; it's that they aren't

properly instructed and exercised.

Simply increasing the driving age by a

year or two doesn't have much influence on the accident rate, for

example. What does make a difference is having a graduated system in

which teenagers slowly acquire both more skill and more freedom—a

driving apprenticeship.

Instead of simply giving adolescents

more and more school experiences—those extra hours of after-school

classes and homework—we could try to arrange more opportunities for

apprenticeship. AmeriCorps, the federal community-service program for

youth, is an excellent example, since it provides both challenging

real-life experiences and a degree of protection and supervision.

"Take your child to work" could become a routine practice rather than

a single-day annual event, and college students could spend more time

watching and helping scientists and scholars at work rather than just

listening to their lectures. Summer enrichment activities like camp and

travel, now so common for children whose parents have means, might be

usefully alternated with summer jobs, with real responsibilities.

The good news, in short, is that we don't have to just accept the

developmental patterns of adolescent brains. We can actually shape and

change them.

—Ms. Gopnik is a professor of psychology at the

University of California, Berkeley, and the author, most recently, of

"The Philosophical Baby: What Children's Minds Tell Us About Truth, Love

and the Meaning of Life." Adapted from an essay that she wrote for www.edge.org, in response to the website's 2012 annual question: "What is your favorite deep, elegant or beautiful explanation?"

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203806504577181351486558984.html

■인구(1939년 기준)

■인구(1939년 기준)

위가 조선의 기생사진이고 아래가 일본의 기생사진입니다. 여러분들은 어느 나라의 기생이더 예쁜가요?

위가 조선의 기생사진이고 아래가 일본의 기생사진입니다. 여러분들은 어느 나라의 기생이더 예쁜가요?

1.신라 왕관

1.신라 왕관

![[TEENCOVER]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AF827B_TEENC_DV_20120127193902.jpg) Harry Campbell

Harry Campbell

![[SB10001424052970204573704577187080963983566]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/RV-AF813_TEENSI_D_20120127181751.jpg)